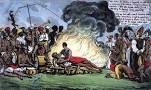

Sati Pratha or tradition of widow burning at the funeral pyre of her husband has been a shameful social evil and an age old practice in Indian society. A widow was burned either with her tacit consent or most of the times forcefully by her in-laws after the death of her husband.

It was banned in 1829, but had to be banned again in 1956 after a resurgence. There was another revival of the practice in 1981 with another prevention ordinance passed in 1987 (Morgan 1984). The idea justifying Sati is that women have worth only in relation to men. This illustrates lack of status as individuals in India.

The burning or burying alive of –

- (i) Any widow along with the body of her deceased husband or any other relative or with any article, object or thing associated with the husband or such relative; or(ii) Any woman along with the body of any of her relatives, irrespective of whether such burning or burying is claimed to be voluntary on the part of the widow or the women or otherwise.Sati has occurred in some rural areas of India, reports extending into the 21st century. Some 30 cases of sati from 1943 to 1987 in the Rajput/Shekavati region are documented according to a referred statistics, the official number being 28. A well-documented case from 1987 was that of 18-year-old Roop Kanwar. In 2002, a 65-year-old woman by the name of Kuttu died after sitting on her husband’s funeral pyre in the Panna district.On 18 May 2006, Vidyawati, a 35-year-old woman allegedly committed sati by jumping into the blazing funeral pyre of her husband in Rari-Bujurg Village, Fatehpur district of Uttar Pradesh.On 21 August 2006, Janakrani, a 40-year-old woman, burned to death on the funeral pyre of her husband Prem Narayan in Sagar district.On 11 October 2008 a 75-year-old woman, Lalmati Verma, committed sati by jumping into her 80-year-old husband’s funeral pyre at Checher in the Kasdol block of Chhattisgarh’s Raipur district.Roop Kanwar was independent India’s 40th sati but the law has done what it should have – made the practice too dangerous to abet. “Most reported cases have taken place in the Shekhawati belt of Rajasthan or in Madhya Pradesh.But even though sati may be simply falling out fashion, but women’s activists and legal experts are worried it may be revived for commercial reasons. India has at least 250 sati temples and the ruling on pujas is too ambiguous to be preventive, they say. Srivastava describes the industry that thrived around Roop Kanwar’s horrific public death. “It was followed by congregations and festivals, and attempts were made to collect funds for the construction of a temple at the site, although the efforts were thwarted after widespread protests and legal intervention.”

A sati temple has always been a big draw. Some temples are thought to be as old as the custom itself, which is believed to have originated 700 years ago among Rajasthan’s ruling warrior community. It was first declared illegal in India as far back as 1829 by Lord William Bentinck, then Governor-General of the East India Company, largely because of Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s activist efforts.

Dr Sarvesh Dhillon, former history professor at Amritsar’s Guru Nanak Dev University, says: “As per the records kept by the Bengal Presidency of the British East India Company, the known occurrences in 1813-1828 were 8,135. Raja Ram Mohan Roy estimated 10 times as many cases of sati in Bengal compared to the rest of the country. In modern times, sati has been largely confined to Rajasthan, with a few instances in the Gangetic plain.”

Dhillon says many Muslim such as Akbar, Jahangir and Aurangzeb, and some Christian rulers have attempted to stop the practice.But almost two centuries after Bentinck’s law and two decades after the anti-sati Act, activists say it is significant that there are discreet congregations at the Rani Sati temple complex in Jhunjhunu, which is called the fountainhead of sati. “Sometimes, the glorification may be difficult to prove as the rituals are conducted in the name of individual pujas,” says Srivastava.

The National Commission for Women recently suggested amendments to the law to prohibit worship at ancient shrines. Kirti Singh, legal convener of the All India Democratic Women’s Association, says the glorification continues “but it is a battle that we can wage because we have the Act, which defines glorification and criminalizes it.”